How Much Of Our Personality Do You Think Is Centered Around Our Biological Makeup Vs, Nurture?

What you'll learn to practice: explain how nature, nurture, and epigenetics influence personality and beliefs

How do we become who nosotros are? Traditionally, people's answers have placed them in i of two camps: nature or nurture. The 1 says genes make up one's mind an individual while the other claims the surround is the linchpin for evolution. Since the 16th century, when the terms "nature" and "nurture" first came into utilize, many people have spent ample time debating which is more than important, but these discussions have more often led to ideological cul-de-sacs rather than pinnacles of insight.

How do we become who nosotros are? Traditionally, people's answers have placed them in i of two camps: nature or nurture. The 1 says genes make up one's mind an individual while the other claims the surround is the linchpin for evolution. Since the 16th century, when the terms "nature" and "nurture" first came into utilize, many people have spent ample time debating which is more than important, but these discussions have more often led to ideological cul-de-sacs rather than pinnacles of insight.

New enquiry into epigenetics—the scientific discipline of how the surroundings influences genetic expression—is irresolute the chat. Every bit psychologist David S. Moore explains in his newest book, The Developing Genome, this burgeoning field reveals that what counts is not what genes you have then much as what your genes are doing. And what your genes are doing is influenced by the ever-changing environment they're in. Factors similar stress, nutrition, and exposure to toxins all play a part in how genes are expressed—essentially which genes are turned on or off. Unlike the static formulation of nature or nurture, epigenetic research demonstrates how genes and environments continuously interact to produce characteristics throughout a lifetime.

Learning Objectives

- Investigate the historic nature vs. nurture debate and describe techniques psychologists use to larn about the origin of traits

- Explicate the basic principles of the theory of development by natural selection, genetic variation, and mutation

The Nature vs. Nurture Debate

Are y'all the way you are because you were born that style, or considering of the way you lot were raised? Do your genetics and biology dictate your personality and behavior, or is it your environment and how you were raised? These questions are central to the historic period-sometime nature-nurture contend. In the history of psychology, no other question has caused so much controversy and offense: We are so concerned with nature–nurture considering our very sense of moral character seems to depend on it. While we may adore the athletic skills of a great basketball game player, we retrieve of his pinnacle equally just a souvenir, a payoff in the "genetic lottery." For the same reason, no one blames a curt person for his peak or someone's congenital inability on poor decisions: To state the obvious, it's "not their fault." Just we do praise the concert violinist (and perhaps her parents and teachers likewise) for her dedication, only as we condemn cheaters, slackers, and bullies for their bad behavior.The trouble is, about human characteristics aren't commonly equally articulate-cut every bit height or musical instrument-mastery, affirming our nature–nurture expectations strongly one way or the other. In fact, even the great violinist might have some inborn qualities—perfect pitch, or long, nimble fingers—that support and reward her hard work. And the basketball player might have eaten a diet while growing up that promoted his genetic tendency for beingness tall. When we think about our own qualities, they seem under our control in some respects, still beyond our command in others. And often the traits that don't seem to have an obvious crusade are the ones that business organisation u.s. the well-nigh and are far more personally significant. What about how much we drinkable or worry? What about our honesty, or religiosity, or sexual orientation? They all come from that uncertain zone, neither stock-still past nature nor totally under our own command.

Effigy 1. Researchers have learned a keen deal about the nature-nurture dynamic by working with animals. Only of course many of the techniques used to study animals cannot be applied to people. Separating these two influences in man subjects is a greater inquiry challenge. [Photo: mharrsch]

Effigy 1. Researchers have learned a keen deal about the nature-nurture dynamic by working with animals. Only of course many of the techniques used to study animals cannot be applied to people. Separating these two influences in man subjects is a greater inquiry challenge. [Photo: mharrsch]

With people, however, we can't assign babies to parents at random, or select parents with certain behavioral characteristics to mate, merely in the interest of scientific discipline (though history does include horrific examples of such practices, in misguided attempts at "eugenics," the shaping of human being characteristics through intentional breeding). In typical human families, children'south biological parents raise them, and then it is very hard to know whether children deed similar their parents due to genetic (nature) or environmental (nurture) reasons. Nevertheless, despite our restrictions on setting up human-based experiments, nosotros do encounter real-world examples of nature-nurture at work in the human sphere—though they only provide partial answers to our many questions. The scientific discipline of how genes and environments work together to influence behavior is calledbehavioral genetics. The easiest opportunity nosotros have to detect this is the adoption study. When children are put up for adoption, the parents who give nascence to them are no longer the parents who raise them. This setup isn't quite the aforementioned as the experiments with dogs (children aren't assigned to random adoptive parents in gild to suit the detail interests of a scientist) but adoption still tells usa some interesting things, or at least confirms some basic expectations. For instance, if the biological kid of tall parents were adopted into a family of short people, do yous suppose the child's growth would exist affected? What about the biological child of a Spanish-speaking family unit adopted at nativity into an English-speaking family? What language would y'all expect the kid to speak? And what might these outcomes tell y'all near the difference betwixt height and linguistic communication in terms of nature-nurture?

Effigy 2. Studies focused on twins have lead to of import insights well-nigh the biological origins of many personality characteristics. [Photo: ethermoon]

Effigy 2. Studies focused on twins have lead to of import insights well-nigh the biological origins of many personality characteristics. [Photo: ethermoon]

At present consider speech communication. If one identical twin speaks Spanish at dwelling, the co-twin with whom she is raised almost certainly does too. But the aforementioned would be true for a pair of fraternal twins raised together. In terms of voice communication, fraternal twins are just equally like as identical twins, and so it appears that the genetic match of identical twins doesn't make much difference. Twin and adoption studies are ii instances of a much broader class of methods for observing nature-nurture called quantitative genetics, the scientific field of study in which similarities among individuals are analyzed based on how biologically related they are. We can do these studies with siblings and half-siblings, cousins, twins who have been separated at nascency and raised separately (Bouchard, Lykken, McGue, & Segal, 1990; such twins are very rare and play a smaller function than is commonly believed in the scientific discipline of nature–nurture), or with entire extended families (see Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2012, for a complete introduction to research methods relevant to nature–nurture).

For meliorate or for worse, contentions about nature–nurture have intensified because quantitative genetics produces a number called a heritability coefficient, varying from 0 to ane, that is meant to provide a unmarried measure of genetics' influence of a trait. In a full general way, a heritability coefficient measures how strongly differences among individuals are related to differences among their genes. But beware: Heritability coefficients, although simple to compute, are deceptively difficult to interpret. Still, numbers that provide uncomplicated answers to complicated questions tend to have a strong influence on the human imagination, and a not bad bargain of fourth dimension has been spent discussing whether the heritability of intelligence or personality or depression is equal to 1 number or some other.

Effigy 3. Quantitative genetics uses statistical methods to study the effects that both heredity and environs accept on test subjects. These methods have provided u.s. with the heritability coefficient which measures how strongly differences among individuals for a trait are related to differences amidst their genes. [Image: EMSL]

Effigy 3. Quantitative genetics uses statistical methods to study the effects that both heredity and environs accept on test subjects. These methods have provided u.s. with the heritability coefficient which measures how strongly differences among individuals for a trait are related to differences amidst their genes. [Image: EMSL]

What Accept Nosotros Learned About Nature–Nurture?

Figure 4. Inquiry over the last half century has revealed how central genetics are to behavior. The more genetically related people are the more similar they are not just physically but also in terms of personality and behavior. [Photo: 藍川芥 aikawake]

Figure 4. Inquiry over the last half century has revealed how central genetics are to behavior. The more genetically related people are the more similar they are not just physically but also in terms of personality and behavior. [Photo: 藍川芥 aikawake]

Whatever the event of our broader discussion of nature–nurture, the basic fact that the best predictors of an adopted child'southward personality or mental health are constitute in the biological parents he or she has never met, rather than in the adoptive parents who raised him or her, presents a significant claiming to purely environmental explanations of personality or psychopathology. The message is clear: You lot can't leave genes out of the equation. Simply keep in mind, no behavioral traits are completely inherited, so you can't go out the environment out altogether, either. Trying to untangle the various means nature-nurture influences homo behavior can be messy, and often mutual-sense notions tin can get in the mode of good scientific discipline. One very pregnant contribution of behavioral genetics that has inverse psychology for good tin be very helpful to keep in mind: When your subjects are biologically-related, no affair how clearly a state of affairs may seem to point to environmental influence, information technology is never prophylactic to translate a behavior as wholly the effect of nurture without further evidence. For example, when presented with data showing that children whose mothers read to them oftentimes are likely to accept better reading scores in third form, it is tempting to conclude that reading to your kids out loud is important to success in school; this may well be true, simply the study as described is inconclusive, because there are genetic as well asenvironmental pathways between the parenting practices of mothers and the abilities of their children. This is a instance where "correlation does not imply causation," as they say. To establish that reading aloud causes success, a scientist tin can either study the problem in adoptive families (in which the genetic pathway is absent) or by finding a way to randomly assign children to oral reading weather.

Try It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/2796

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/2797

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/2798

Think It Over

- Is your personality more like one of your parents than the other? If you accept a sibling, is his or her personality like yours? In your family, how did these similarities and differences develop? What do you think acquired them?

- Can y'all think of a man feature for which genetic differences would play well-nigh no office? Defend your choice.

- Practise you think the time volition come when nosotros will exist able to predict well-nigh everything nearly someone by examining their Deoxyribonucleic acid on the day they are born?

- Identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins for the trait of aggressiveness, besides every bit for criminal behavior. Do these facts have implications for the court? If it can be shown that a trigger-happy criminal had tearing parents, should information technology make a departure in culpability or sentencing?

Psychological researchers study genetics in lodge to better understand the biological footing that contributes to certain behaviors. While all humans share certain biological mechanisms, we are each unique. And while our bodies take many of the same parts—brains and hormones and cells with genetic codes—these are expressed in a wide multifariousness of behaviors, thoughts, and reactions.

Why do ii people infected by the same illness have unlike outcomes: one surviving and ane succumbing to the disquiet? How are genetic diseases passed through family lines? Are there genetic components to psychological disorders, such every bit depression or schizophrenia? To what extent might in that location be a psychological ground to health atmospheric condition such as babyhood obesity?

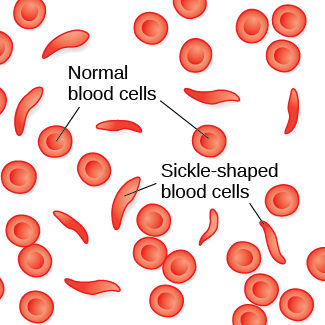

To explore these questions, let's start by focusing on a specific disease, sickle-cell anemia, and how it might bear upon two infected sisters. Sickle-cell anemia is a genetic status in which red blood cells, which are normally circular, take on a crescent-like shape (Effigy five). The changed shape of these cells affects how they office: sickle-shaped cells can clog blood vessels and block blood flow, leading to loftier fever, astringent pain, swelling, and tissue impairment.

Figure v. Normal blood cells travel freely through the blood vessels, while sickle-shaped cells course blockages preventing blood flow.

Figure v. Normal blood cells travel freely through the blood vessels, while sickle-shaped cells course blockages preventing blood flow.

Many people with sickle-cell anemia—and the particular genetic mutation that causes information technology—die at an early on age. While the notion of "survival of the fittest" may suggest that people suffering from this disease take a low survival rate and therefore the disease volition become less common, this is not the case. Despite the negative evolutionary effects associated with this genetic mutation, the sickle-cell gene remains relatively common among people of African descent. Why is this? The caption is illustrated with the post-obit scenario.

Imagine two young women—Luwi and Sena—sisters in rural Zambia, Africa. Luwi carries the cistron for sickle-cell anemia; Sena does not bear the gene. Sickle-cell carriers have 1 copy of the sickle-cell factor but do not have full-diddled sickle-cell anemia. They experience symptoms merely if they are severely dehydrated or are deprived of oxygen (as in mountain climbing). Carriers are thought to be immune from malaria (an often mortiferous disease that is widespread in tropical climates) because changes in their blood chemistry and immune performance foreclose the malaria parasite from having its effects (Gong, Parikh, Rosenthal, & Greenhouse, 2013). However, full-blown sickle-cell anemia, with two copies of the sickle-cell gene, does non provide amnesty to malaria.

While walking domicile from school, both sisters are bitten past mosquitos carrying the malaria parasite. Luwi does not get malaria considering she carries the sickle-cell mutation. Sena, on the other manus, develops malaria and dies just two weeks later. Luwi survives and somewhen has children, to whom she may pass on the sickle-cell mutation.

Malaria is rare in the U.s.a., and then the sickle-jail cell gene benefits nobody: the gene manifests primarily in health bug—minor in carriers, severe in the full-blown disease—with no health benefits for carriers. However, the situation is quite different in other parts of the earth. In parts of Africa where malaria is prevalent, having the sickle-cell mutation does provide health benefits for carriers (protection from malaria).

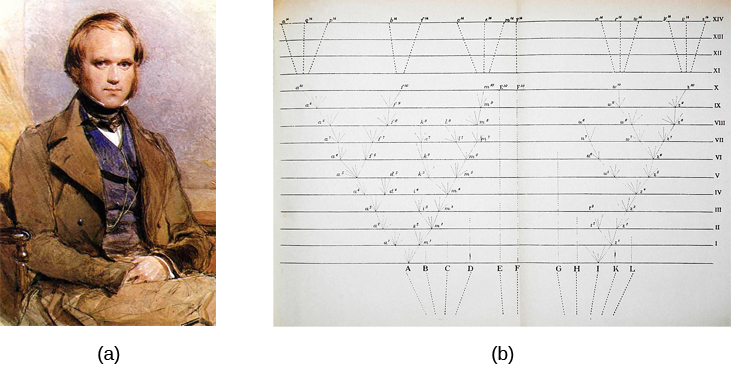

This is precisely the state of affairs that Charles Darwin describes in the theory of evolution by natural selection (Effigy six). In elementary terms, the theory states that organisms that are better suited for their environment will survive and reproduce, while those that are poorly suited for their environment volition die off. In our example, nosotros tin meet that as a carrier, Luwi'south mutation is highly adaptive in her African homeland; all the same, if she resided in the United States (where malaria is much less mutual), her mutation could prove costly—with a high probability of the affliction in her descendants and minor health problems of her own.

Figure 6. (a) In 1859, Charles Darwin proposed his theory of evolution by natural selection in his book, On the Origin of Species. (b) The book contains just ane analogy: this diagram that shows how species evolve over time through natural selection.

Figure 6. (a) In 1859, Charles Darwin proposed his theory of evolution by natural selection in his book, On the Origin of Species. (b) The book contains just ane analogy: this diagram that shows how species evolve over time through natural selection.

Dig Deeper: Two Perspectives on Genetics and Behavior

Information technology's easy to get confused nigh two fields that study the interaction of genes and the environment, such as the fields of evolutionary psychology and behavioral genetics. How can we tell them autonomously?

In both fields, it is understood that genes non simply code for particular traits, but as well contribute to certain patterns of cognition and behavior. Evolutionary psychology focuses on how universal patterns of behavior and cognitive processes accept evolved over time. Therefore, variations in cognition and behavior would brand individuals more or less successful in reproducing and passing those genes to their offspring. Evolutionary psychologists report a variety of psychological phenomena that may have evolved as adaptations, including fear response, food preferences, mate pick, and cooperative behaviors (Confer et al., 2010).

Whereas evolutionary psychologists focus on universal patterns that evolved over millions of years, behavioral geneticists study how individual differences arise, in the present, through the interaction of genes and the environment. When studying human behavior, behavioral geneticists often utilize twin and adoption studies to research questions of involvement. Twin studies compare the rates that a given behavioral trait is shared amid identical and fraternal twins; adoption studies compare those rates amid biologically related relatives and adopted relatives. Both approaches provide some insight into the relative importance of genes and environment for the expression of a given trait.

Try It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/2799

Genetic Variation

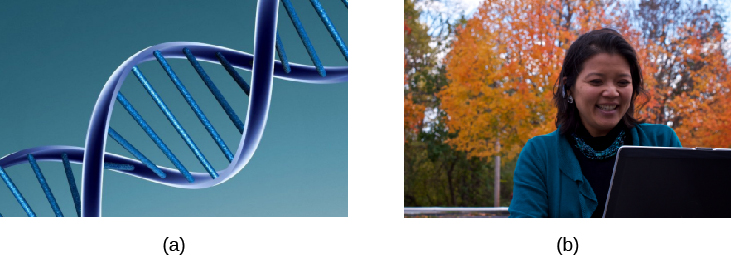

Genetic variation, the genetic difference betwixt individuals, is what contributes to a species' adaptation to its environment. In humans, genetic variation begins with an egg, about 100 million sperm, and fertilization. Fertile women ovulate roughly once per month, releasing an egg from follicles in the ovary. The egg travels, via the fallopian tube, from the ovary to the uterus, where it may be fertilized by a sperm.The egg and the sperm each contain 23 chromosomes. Chromosomes are long strings of genetic textile known every bit deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). DNA is a helix-shaped molecule made upward of nucleotide base pairs. In each chromosome, sequences of DNA make upward genes that control or partially control a number of visible characteristics, known as traits, such as eye color, pilus color, and and then on. A single factor may take multiple possible variations, or alleles. An allele is a specific version of a gene. And so, a given gene may code for the trait of hair colour, and the different alleles of that factor affect which hair color an individual has.

When a sperm and egg fuse, their 23 chromosomes pair up and create a zygote with 23 pairs of chromosomes. Therefore, each parent contributes half the genetic information carried by the offspring; the resulting physical characteristics of the offspring (chosen the phenotype) are determined past the interaction of genetic textile supplied past the parents (called the genotype). A person's genotype is the genetic makeup of that individual. Phenotype, on the other hand, refers to the individual'south inherited physical characteristics (Figure vii).

Figure 7. (a) Genotype refers to the genetic makeup of an individual based on the genetic cloth (DNA) inherited from one'due south parents. (b) Phenotype describes an individual's observable characteristics, such every bit hair color, skin color, top, and build. (credit a: modification of piece of work by Caroline Davis; credit b: modification of work by Cory Zanker)

Figure 7. (a) Genotype refers to the genetic makeup of an individual based on the genetic cloth (DNA) inherited from one'due south parents. (b) Phenotype describes an individual's observable characteristics, such every bit hair color, skin color, top, and build. (credit a: modification of piece of work by Caroline Davis; credit b: modification of work by Cory Zanker)

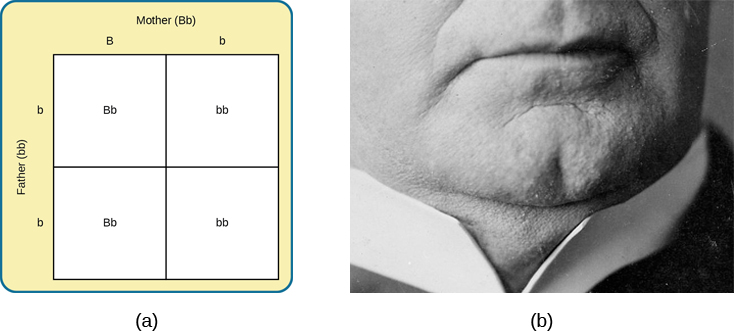

Most traits are controlled by multiple genes, but some traits are controlled past ane gene. A feature like scissure chin, for example, is influenced past a unmarried gene from each parent. In this example, nosotros will telephone call the gene for crevice mentum "B," and the cistron for smooth chin "b." Cleft mentum is a dominant trait, which means that having the dominant allele either from one parent (Bb) or both parents (BB) volition always outcome in the phenotype associated with the dominant allele. When someone has two copies of the aforementioned allele, they are said to be homozygous for that allele. When someone has a combination of alleles for a given factor, they are said to be heterozygous. For case, smoothen chin is a recessive trait, which means that an individual volition only display the smooth chin phenotype if they are homozygous for that recessive allele (bb).

Imagine that a adult female with a crevice chin has a child with a man with a polish chin. What type of chin will their child have? The answer to that depends on which alleles each parent carries. If the adult female is homozygous for cleft chin (BB), her offspring will always take cleft chin. It gets a little more complicated, however, if the mother is heterozygous for this gene (Bb). Since the father has a smooth chin—therefore homozygous for the recessive allele (bb)—we can expect the offspring to have a 50% take a chance of having a crevice chin and a 50% chance of having a shine mentum (Figure 8).

Figure 8. (a) A Punnett square is a tool used to predict how genes will interact in the production of offspring. The majuscule B represents the ascendant allele, and the lowercase b represents the recessive allele. In the example of the fissure chin, where B is fissure chin (dominant allele), wherever a pair contains the dominant allele, B, you tin can expect a crevice chin phenotype. You lot can expect a smooth chin phenotype simply when there are two copies of the recessive allele, bb. (b) A cleft chin, shown here, is an inherited trait.

Figure 8. (a) A Punnett square is a tool used to predict how genes will interact in the production of offspring. The majuscule B represents the ascendant allele, and the lowercase b represents the recessive allele. In the example of the fissure chin, where B is fissure chin (dominant allele), wherever a pair contains the dominant allele, B, you tin can expect a crevice chin phenotype. You lot can expect a smooth chin phenotype simply when there are two copies of the recessive allele, bb. (b) A cleft chin, shown here, is an inherited trait.

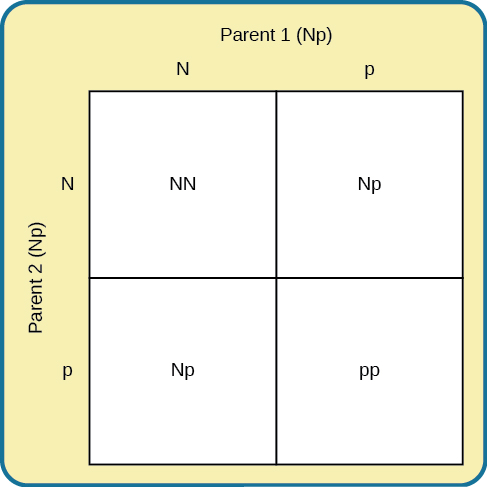

Sickle-prison cell anemia is merely one of many genetic disorders caused by the pairing of ii recessive genes. For example, phenylketonuria (PKU) is a condition in which individuals lack an enzyme that normally converts harmful amino acids into harmless byproducts. If someone with this condition goes untreated, he or she will experience significant deficits in cerebral function, seizures, and increased risk of various psychiatric disorders. Considering PKU is a recessive trait, each parent must take at least one copy of the recessive allele in order to produce a kid with the condition (Figure ix).

Figure 9. In this Punnett square, North represents the normal allele, and p represents the recessive allele that is associated with PKU. If two individuals mate who are both heterozygous for the allele associated with PKU, their offspring accept a 25% chance of expressing the PKU phenotype.

Figure 9. In this Punnett square, North represents the normal allele, and p represents the recessive allele that is associated with PKU. If two individuals mate who are both heterozygous for the allele associated with PKU, their offspring accept a 25% chance of expressing the PKU phenotype.

And then far, nosotros have discussed traits that involve merely ane gene, but few human being characteristics are controlled by a single cistron. Nearly traits are polygenic: controlled by more than one gene. Height is 1 example of a polygenic trait, as are skin color and weight.

Where do harmful genes that contribute to diseases like PKU come from? Gene mutations provide one source of harmful genes. A mutation is a sudden, permanent alter in a factor. While many mutations can be harmful or lethal, once in a while, a mutation benefits an individual past giving that person an advantage over those who practise not accept the mutation. Call up that the theory of evolution asserts that individuals best adapted to their item environments are more likely to reproduce and pass on their genes to future generations. In order for this process to occur, at that place must exist competition—more technically, at that place must be variability in genes (and resultant traits) that allow for variation in adaptability to the environment. If a population consisted of identical individuals, then whatever dramatic changes in the environment would affect everyone in the same mode, and there would be no variation in option. In dissimilarity, multifariousness in genes and associated traits allows some individuals to perform slightly better than others when faced with ecology modify. This creates a singled-out advantage for individuals best suited for their environments in terms of successful reproduction and genetic manual.

Effort It

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/2800

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/2801

https://assessments.lumenlearning.com/assessments/4201

Glossary

adoption study: a beliefs genetic research method that involves comparison of adopted children to their adoptive and biological parents

allele:specific version of a gene

behavioral genetics: the empirical science of how genes and environments combine to generate behavior

chromosome:long strand of genetic information

dna (DNA):helix-shaped molecule made of nucleotide base pairs

dominant allele:allele whose phenotype will be expressed in an individual that possesses that allele

genetic ecology correlation:view of gene-environs interaction that asserts our genes impact our environment, and our environment influences the expression of our genes

genotype:genetic makeup of an private

heterozygous:consisting of two different alleles

heritability coefficient: an hands misinterpreted statistical construct that purports to measure the role of genetics in the explanation of differences among individuals

homozygous:consisting of two identical alleles

mutation:sudden, permanent change in a gene

phenotype:individual's inheritable concrete characteristics

polygenic:multiple genes affecting a given trait

quantitative genetics: scientific and mathematical methods for inferring genetic and environmental processes based on the degree of genetic and ecology similarity amid organisms

recessive allele:allele whose phenotype will be expressed simply if an individual is homozygous for that allele

theory of evolution past natural pick:states that organisms that are improve suited for their environments will survive and reproduce compared to those that are poorly suited for their environments

twin studies: a behavior genetic enquiry method that involves comparison of the similarity of identical (monozygotic; MZ) and fraternal (dizygotic; DZ) twins

Licenses and Attributions

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-psychology/chapter/outcome-gene-environment-interaction/

Posted by: steigerwaldducke1954.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Of Our Personality Do You Think Is Centered Around Our Biological Makeup Vs, Nurture?"

Post a Comment